Our Story

1959: The National Capital Historical Museum of Transportation, Inc. (NCTM) is founded.

January 28th, 1962: Final date of street car service in Washington, DC. Founding members of NCTM are the last to ride!

1965-1966: An agreement with Montgomery Parks is reached in Northwest Branch Park; the museum is given 7 acres for a museum and railway. Groundbreaking for the first car barn begins in November 1965. Groundbreaking for the Visitor Center begins in August 1966.

1969: Work on the railway begins. By May, tracks are completed to the Fishhook siding, which remains part of our railway today. On September 9th, the first trip under 600 volts is taken by Vienna 6062, and on October 17th, operations at the National Capital Trolley Museum officially begin!

1970-1975: Railway operations extend to Fishhook siding (1970) and Dodge Loop (1975). A second car barn is constructed to house a growing collection of cars in 1971.

2003: A fire in one of the car barns results in the tragic loss of eight street cars.

2008: With the building of the Intercounty Connector highway slated to run straight through NCTM’s land, an agreement is reached to move the museum to its present location off Bonifant Road, with brand new facilities. Operations are suspended in preparation.

2010: The Museum reopens at its present location.

2019: National Capital Trolley Museum celebrates its 50th Anniversary on October 17th.

2020: Public operations are suspended due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

2021: Public operations resume. Welcome back!

Founding members review plans for the museum, 1967.

Children enjoy a hands-on school program, c. 2013

Betty and John stand with TTC 4602, date unknown.

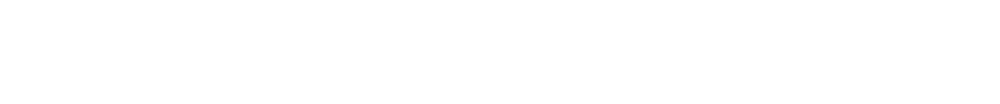

Long time volunteer Bob Schnabel clearing ice storm damage from the tracks, January 2002.

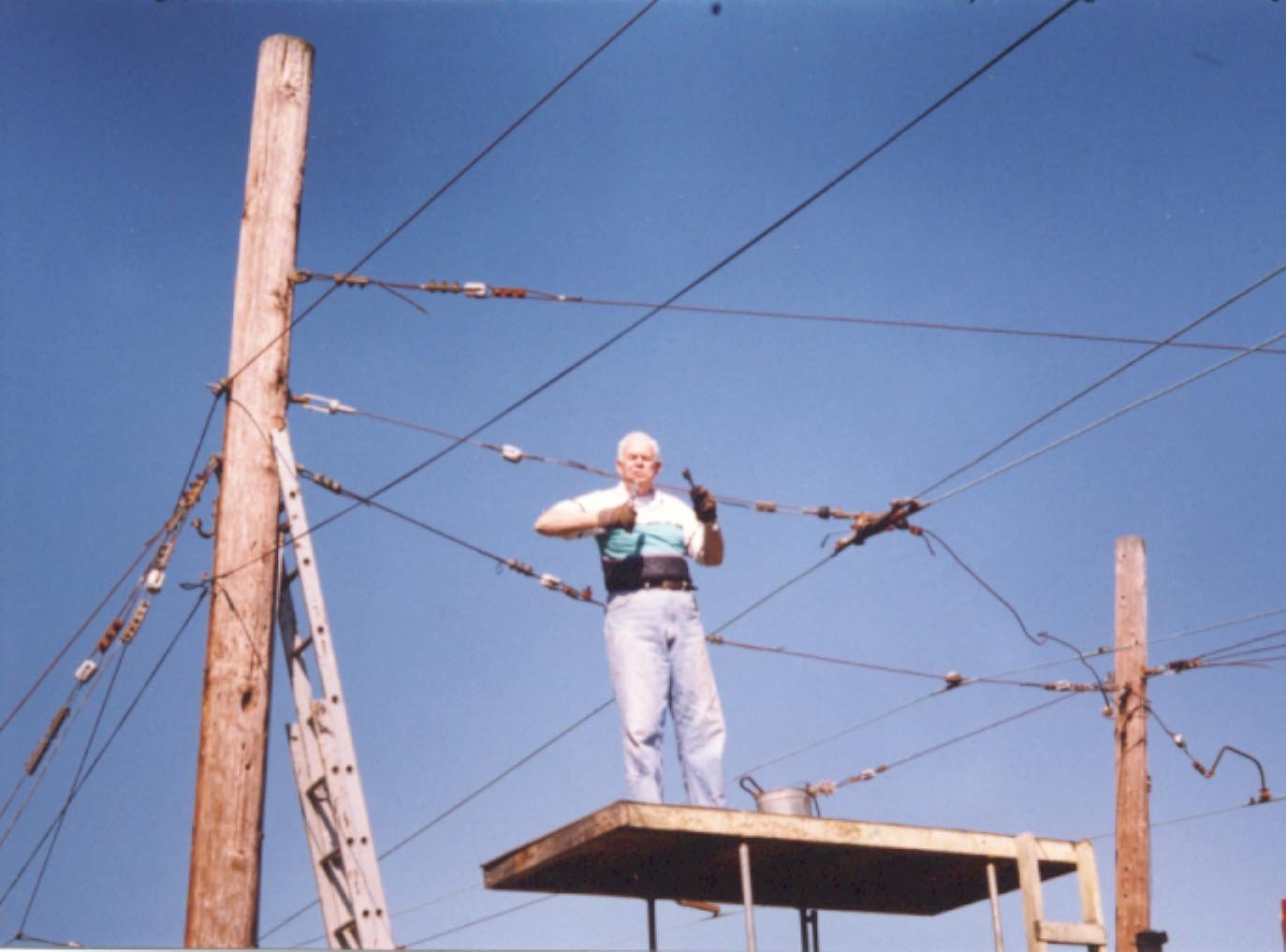

Bob Schnabel working on the overhead, January 2002.

Volunteers all smiles on BTS 606 on May 15th, 2018.

Volunteers taking CTCo 522 out for a spin before its full restoration shortly thereafter. Photo taken on October 25th, 2011.

Passengers enjoying a rumble down the line in TTC 4602, March 2011.

Volunteers Eric and Rodger repairing the wire with the help of #5221 on September 24th, 2011.

Eric and Bob collaborating on the restoration of HTM 1329; January 9th, 2011.

Eric doing some work on top of HTM 1329; January 9th, 2011.

Putting the finishing touches on the gift shop in the new building, 2010.

A beautiful day with HTM 1329, TTC 4602, and STIB 1069 poised for service on September 1st, 2015.

Carol Petzold coordinating and hosting a Volunteer Appreciation event on May 9th, 2015.

Keith Bray tacking canvas, date unknown.

Visitors making crafts with Joanie Pinson (in white), who was NCTM's Education Director at the time. Photo taken 2012.

Founding member Vernon Winn giving a talk in front of CTCo 09, c. 2012.

Joanie Pinson leads a children's activity, c. 2012.

Electric Street Cars in the Nation’s Capital

The following are edited excerpts from “Street Cars in the Nation’s Capital,” by Wesley Paulson and Ken Rucker. For the full article, click here.

The development of the electric street railway dramatically altered the lives of Americans and grew into an industry of 44,800 miles of track; 295,000 employees; and 11.3 billion passengers by 1917. Factory workers moved to better housing some distance from their places of employment. Middle-class families created the suburbs. Farmers became less isolated from nearby towns. Commercial and entertainment centers prospered as the developing mass society moved to the tune of the singing trolley wire.

The mayor and city council pose before inspecting the new trolley line from Laurel, MD to DC. September 21, 1902. NCTM Collections.

1897 - 1931: From Cable to Conduit

In Washington, DC, following the spectacular fire which destroyed its cable power house in 1897, the Capital Traction Company (CTCo) installed in its cable conduit power rails and insulators following the design brought to Washington from New York City by the Metropolitan Railroad in 1895. The success of this underground electric conduit system, a piece of which you can see in National Capital Trolley Museum’s Conduit Hall, meant the end of horse and cable traction in the Nation’s Capital.

Within only nine months, CTCo electrified its system and purchased seventy closed motor cars (including CTCo 522, on display in Street Car Hall) from the American Car Company of St. Louis. This rapid transformation continued the reliance on trains of small street cars, until 1906 with the gradual transition to larger double-truck cars from Cincinnati Car Company and the J.G. Brill Company with more from the Jewett Car Company in 1910-12.

Looking forward to improving service, CTCo subscribed to the Electric Railway Presidents’ Conference Committee (PCC) for $10,900 in 1930 and completed in 1931 the modernization of sixty cars that had been modernized in 1918-19. Over the next few decades, WRECo and CTCo added sixty-two center-entrance and 142 deck-roof cars to their fleets, along with smaller orders of center-door cars and railroad-roof, double-end “Rockville” cars.

The motorman and conductor of CTCo motor car 401 and trailer 1401 pose at Rock Creek Loop along Calvert Street. NCTM Collections.

1931 - 1956: Glen Echo Park and the PCC Car

Like hundreds of amusement parks across the nation, Glen Echo Park developed as a creature of a trolley company and a destination for thousands of revelers who fled the city on the WRECo’s cars. For 44 years, the trolley company owned the Glen Echo Park Company which became the primary amusement center of the National Capital area.

In 1933, CTCo and WRECo merged to form the Capital Transit Company (CTC). Utilizing a well-maintained but dated fleet, the new organization provided nearly all the street railway service and the bulk of motor bus service in the District of Columbia. The firm’s new program included the introduction of a weekly pass and wider transfer privileges, rationalizations of duplicate facilities, and rerouting of service offer to its patrons. Management embarked on a modernization program which resulted in acquisitions totaling 1012 street cars and buses between 1935 and 1941. The sizeable progress CTC made in placing new equipment like the Presidents’ Conference Committee (PCC) car into service enabled the CTC to survive the Depression and to meet the challenges of World War II.

Map showing the 1936 reroutings in DC’s downtown. NCTM Collections.

CTCo 1259 inbound from Cabin John stops for a lone passenger at Glen Echo park entrance on May 16th, 1941. NCTM Collections.

1955 - 1962: Farewell to DC Street Cars… For Now!

After World War II, CTC invested in new equipment and construction of the Dupont Circle street car subway. Required divestiture of North American Company holdings ended the forty-seven year link between Washington’s street railways and electric power utility as CTC was sold to an investment group. New management distributed large cash reserves to maintain a 7.5% rate of return to stockholders. To continue these payments, CTC coupled union demands for higher wages to its need for higher fares. The resulting stroke in the summer of 1955 prompted Congress to pass Public Law 389 which lifted CTC’s franchise on August 14th, 1956.

Service continued as usual a day later on August 15th under the name D.C. Transit System. The new buyer, O. Roy Chalk, experimented with street car improvements, proposed a trolley subway under Seventh Street and Georgia Avenue, and introduced an air-conditioned tourist car called the Silver Sightseer (DCTS 1512), but ultimately street cars were destined to be taken out of service. By January 28th, 1962, all street car services in DC had been converted to buses.

The Silver Sightseer (DCTS 1512) had air conditioning, fluorescent lighting, high back seats, and an onboard hostess to describe the city’s sights! NCTM Collections.

2002 - Present Day: DC Streetcar and the H-Street Line

The idea for bringing street cars back to the Nation’s Capital came from Metro (WMATA) in 2002, though funding issues delayed, postponed, and ended some of those plans. Eventually a 2004 revised plan was approved and funded by the District of Columbia, and the project started to move forward slowly. The city began to lay track in the Anacostia and Benning neighborhoods, chosen for the purpose of improving their commercial corridors and because those areas had been the last to receive Metro service. The Washington Business Journal reported on the proposed street car lines in 2007, citing street cars as the DC municipalities’ response to worsening congestion in the District. As with the street cars of the past, they also hoped to improve transit for tourists looking to enjoy themselves and see the city. As of 2010, work on the Anacostia line has been halted due to the expiry of construction contracts.

On February 27th, 2016, the DC Streetcar system on the H Street/Benning Road Line began public service. The line travels between Union Station and Oklahoma Avenue. There are currently six articulated street cars in service, ordered in 2005 and made by Inekon Trams in the Czech Republic. In 2021, ridership was 285,000. Perhaps you were one of those riders!

What could the next fifty years in DC street car transit bring? How will street cars continue to grow, shape, and change our communities?

DC Streetcar at Union Station stop at the end of the H Street NE line. By Mariordo (Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz) - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.